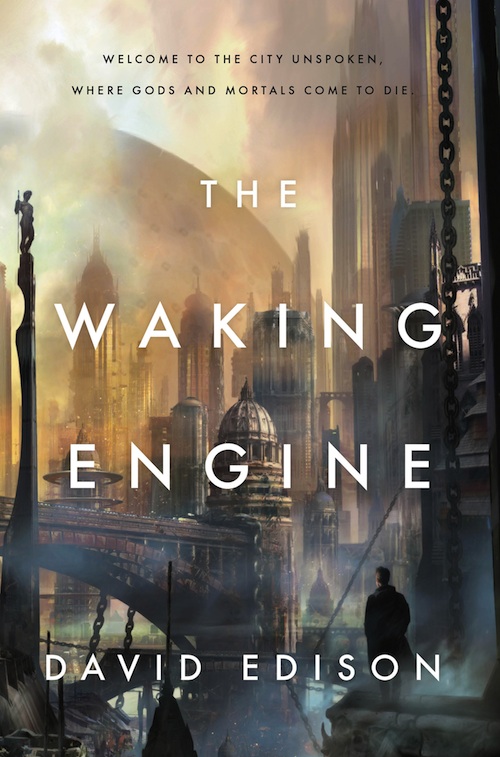

Check out David Edison’s debut novel, The Waking Engine, available February 11th from Tor Books!

Contrary to popular wisdom, death is not the end, nor is it a passage to some transcendent afterlife. Those who die merely awake as themselves on one of a million worlds, where they are fated to live until they die again, and wake up somewhere new. All are born only once, but die many times… until they come at last to the City Unspoken, where the gateway to True Death can be found.

Wayfarers and pilgrims are drawn to the City, which is home to murderous aristocrats, disguised gods and goddesses, a sadistic faerie princess, immortal prostitutes and queens, a captive angel, gangs of feral Death Boys and Charnel Girls… and one very confused New Yorker.

My braying heart continues in spite of itself: I am. I am. I am.

I do not know why I am here, but it is clearly not to Die. I see them, the Dying people, spiritually aged, faces bleached of all color by worlds of weekdays; I see them stumbling through the cathedral forest beneath the Dome. My God, I think they are like birds. Piloted by instinct.

I’ll spend hours birdwatching there, watching them Die—their bodies evaporate like smoke and the last look on their faces is peace, the first true peace they have known in dozens or hundreds or thousands of lives. Peace comes like a broken clock.

I hate them for that, the idiot birds who get to Die. If it were within my power to deny the Dying their Deaths, I would. Why should they find peace while I find none?

—Sylvia Plath, Empty Skies & Dying Arts

Cooper opened his eyes to see a spirit shaped like a woman, who cradled his head in her hands, her hair a halo of pink light that fell over his face. Angel eyes the color of wet straw looked down on him, and she smelled of parchment and old leather. As his eyes adjusted to the light, he saw that her freckled skin was tan, nearly brown, and for a long moment Cooper waited for her to speak. This is heaven, she would say. You will find peace here, and oblivion. We will heal your hurts, friend. Welcome home, she would say. You have been away too long. Cooper would smile, and submit, and she would guide him somewhere radiant.

He did not expect the slap to his cheek. Nor the second that followed, stinging.

He did not expect the angel to drop his head onto the hard ground and declaim, “I can do nothing with this turd.”

“My friend was not wrong, Sesstri,” a man said, cursing. “That is what makes him my friend and not my dinner.”

The woman pulled away and light came pouring over Cooper’s eyes, almost as blinding as before. Struggling, he could see that it wasn’t the light of heaven needling through his pupils—the sky above was jaundiced and cloud-dappled, and he lay in the rain on an odd little hillock that bristled with yellow grass. Above him, the two strangers just stood there, glaring down at his body.

And suddenly his body was all Cooper could feel: lit up with pain, scalded. How had he thought himself dead, let alone at peace? His bones ached and his bowels shuddered, and an abrupt crack of lightning overhead seemed to pierce his skull and live there, screeching agony between his temples. He tried to sit up but couldn’t. He couldn’t even roll onto his side, and when Cooper opened his mouth no words came out—he jawed like a fish in air, and flopped as helplessly. Flocks of birds pinwheeled across the sky. Bells rang and rang.

What happened? Cooper scrambled inside his head to reassemble some kind of continuity of experience. The last thing he could recall was drifting through a borderless sleep into a half-dream of lightless depths. He recalled sensing bodies in motion, masses larger than planets drifting through the murk below his dream-self. He could not see them, but somehow—he knew them. And maybe then he had passed beyond shadows. Maybe then he’d seen a city.…

“Bells for the abiding dead, what a waste of my time!” The man standing above Cooper cursed again and raised his boot. Cooper had time to blink once before the crunch of boot-heel slammed him back into darkness.

When he next opened his eyes, Cooper could tell by the quality of the light that he’d been moved indoors. He heard voices, the same man and woman from earlier, still arguing. He’d been dropped onto something hard but covered in padding, and when the wood creaked beneath his weight and a pillow found his cheek, he realized it was a sofa. Something about creaking wood and narrow cushions felt instantly recognizable; for half a second, Cooper worried that he’d broken the furniture, an old, familiar thought. He closed his eyes before anyone could see he’d come around, playing detective with his senses as rapidly as his addled mind could muster. He smelled kitchen smells—soap and old food—and something pleasant, like flowers or potpourri. Peeking out from between his lashes, Cooper saw a blurry image of his saviors—captors?—the man and woman who’d taken him home.

“I’ve finished examining him, Asher. You can come back in.” The woman, who sounded annoyed, smoothed strawberry-blond hair so pale it fell past her shoulders like a bolt of pink silk. “I cannot help you with this. Anything your friend said you’d find on that hill is between you and the sheep guts, or whatever absurd claptrap he employs to disabuse you of your coin. I’m not going to rifle through every corpse that wakes up south of Displacement and Rind for you, anyway, so you’ll have to do the dirty work yourself.”

“Fine, forfeit your fee, Sesstri,” said Asher, and Cooper noticed that the tall man, broad-shouldered but gaunt, had skin and hair the pale gray of old bones or nearly pregnant clouds. “I’d pay you for examining his body, but since I carried him back to your house, I think we’re even.”

Cooper squeezed his eyes shut again and felt them approach, felt them hover over him.

“He’s as heavy as he looks,” said the gray man.

Sesstri made an unhappy noise. Cooper didn’t need eyes to feel her scrutiny. He kept still when she jabbed his chest with her finger.

When she spoke, Cooper could tell that Sesstri had turned away. “He is just a person. He’s just like everyone else.” She hesitated. “A little green to wake up here, but nothing unheard of—I only died twice before I came here myself. Whoever he may have been, he is not the ‘something special’ you are looking for. He will heal no wounds, diagnose no conditions, and answer no questions.” She left the room, seeming more interested in the singing teakettle than the men defiling her home. “Muck up the place all you like,” she called out, “I haven’t seen the landlady since the day she handed me the keys.”

Asher knelt close and brushed Cooper’s face with his hand. “You can open your eyes now, friend. We don’t need her.” He whispered, tobacco on his breath, and Cooper peeked through his eyelids. The face so close to his own was a silver mask that smiled: “Welcome to the City Unspoken, where the dead come to Die. In my city, everything old is made new again, and anything new is devoured like sweet eel candy.”

Cooper looked at Asher’s ghostlike hair as he pulled away and turned to stir something at the sink beneath the window. Over his shoulder, the window showed a square of lemony sky and an unfamiliar, pale green sun. When Cooper sat up, head throbbing, Asher turned to him holding a tray piled with buttered toast and two steaming mugs. His gray skin was smooth and his eyes flickered like strange candles, red and blue and green together. He was handsome and repulsive at the same time, like a great beauty embalmed. Something wriggled inside Cooper’s head, an instinct trying to name itself. It didn’t come.

Nothing came, Cooper realized—no panic, no outrage, no bewilderment or dispossession at waking to find himself… well… wherever he’d found himself. Nothing came but fog in his mind and an emptyheaded sense of confusion.

Asher smirked when he saw Cooper awake, but said nothing, content to lean on his hip and observe the new arrival. The moment stretched. Then it snapped. “What…” Cooper blurted, then faltered, unable to pick one question from the dozens that crowded his tongue. “Why is the sun green?”

The last thing Cooper remembered was lying down fully clothed on his own bed after another long day of work and text messages. But these weren’t his friends, this wasn’t his apartment, and he certainly hadn’t been sending texts to any ash-skinned thugs. All he knew for certain— this was no dream. It hurt too much, and the logic didn’t follow itself moment-to-moment as in a dream.

“Welcome to the waking,” Asher said with a smile. “Drink this.” His long-fingered hands were huge.

“Sesstri’s taking notes.” He handed Cooper a mug steaming with the scent of jasmine and spice. “I left the room while she strip-searched you, though, if that spares your ego any.”

Cooper looked down at the mug shaking in his hands and fought the urge to throw it in the stranger’s face. His gut, as always, told him to say “fuck you,” and, as always, he said nothing. He grimaced, though the tea and buttered bread smelled like heaven.

“Drink it,” Asher commanded.

Jasmine and pepper filled his mouth, hot and real. And it did bring Cooper back, clearing some of the fog from his head. He began looking at his surroundings in earnest while rolling sips of tea across his dry tongue. They sat alone in a room, the wallpaper calligraphed with unfamiliar symbols. On a wooden table against one wall spun an oddlooking Victrola, its mouthpiece carved from a huge spiral horn, and a low table piled with books. In fact, every available surface seemed piled with books. Asher handed him a plate and this time Cooper accepted it eagerly.

“This is a living room,” Cooper said before filling his mouth with toast. It was bliss.

“Ah, yes. It is. I’m Asher.” The gray stranger introduced himself, nodding.

Cooper reciprocated through a mouthful of buttery ecstasy. “Maybe you could… tell me… where I am?” he added.

Asher watched Cooper scarf down the toast and drain the spicy tea, then held out a hand. “Can you stand? Come upstairs with me, and I will show you.”

Of course I can stand, Cooper thought before trying—and falling back onto the couch. He frowned and grabbed another slice of toast as Asher lugged him to his feet, but a few steps later his legs weren’t so wobbly after all.

He followed Asher up a narrow stairway that turned at odd angles and led higher than Cooper felt it ought to. At one pinched landing stood an end table where an armful of foxglove shoots wilted from a china vase. “She can’t be bothered with flowers…” Asher half muttered, shaking his head.

At the top of the stairs, the gray man opened a splintered door with a kind of reverence. Sweeping one smoky hand, he ushered Cooper through the portal.

As he stepped out onto the wooden widow’s walk nailed to the roof, a chill passed through Cooper’s body. A city lay spread out before him. More than a city—a comment on a city, on all cities, a sprawling orgy of architectural imagination and urban decay. Buildings and blocks stretched to the horizon, and Cooper’s head reeled to take it in, from the spired heights that pierced the distance to the crusts of abandoned blocks, smoldering and dark where they lay. He turned and turned, but the city was all he could see, opening itself to him. There were wards that seemed to bustle with life, but there were also dead zones—whole precincts left to rot within the girding chaos. What he saw seemed to be the very idea of a city, barnacled and thick with itself.

Veils of fog hung at various altitudes within the air, draped over the city in colors of rock crystal—smoky quartz, amethyst, and citrine. The wind was strangely warm, and Cooper smelled a dozen different flavors of incense on its shifting gusts. A song of competing bells tolled point and counterpoint across the metropolis, sending flocks of birds wheeling into the air at intervals.

And competing skies. The pale yellow sky that Cooper had seen through the window downstairs seemed to have slid off to one side of the heavens, following its tiny green star. In the east, heavy clouds played peekaboo with a bluer firmament, and a yellow sun seemed to emerge, fading into and out of existence as he watched.

The skies, he marveled, watching them change.

Asher led Cooper, dumbfounded, to a weathered spyglass mounted upon a pipe at the edge of the walkway. Cooper hesitated—did he want to see? Did he want to accept the reality of this fever-dream? But he put his face to the glass and opened his eye to the city, despite suspecting that once he saw the details of this nightmare, once he knew its shape and aspect, it would be irreversibly real. The city would be real and he would be well and truly lost within it, unhinged, a ghost among ghost-men.

Through the telescope he saw snapshots of the whole: monuments and mausoleums pitted and scarred with age lay tilted, stone and gilt akimbo as the growth of the city slowly devoured them. Mansions hid behind walls that sheltered riotous gardens and skeletal gazebos. To the west, a sculpture of a weeping woman worked entirely in silver sat buried up to her massive head in newer stonework—a garland of exhaust pipes about her neck belched bruise-purple smoke into the air from below. Not far from that, an alabaster angel blew his shofar before a ramshackle square that brimmed with black oil, summoning a host that would clearly never come. And chains, everywhere chains—thick as houses, exposed by canals, or pulled up from belowground and winched like steeples over bridges and buildings, draped across districts, erupting from the tiled floors of public squares.

Panning, Cooper saw wide boulevards lined with sycamores, elms, and less familiar trees, avenues that glittered darkly or pulsed with traffic. The larger thoroughfares led from a shadowy axis that reminded him of an orb spider’s web. At the center of the web, near the horizon, a vast plaza yawned. The plaza itself must have been huge to be so visible from this distance, but what lay beyond was bigger still: was it a structure, or a mountain, or something still more bizarre?

Above the central space loomed a dome that would dwarf a hundred arenas, a hemisphere worked in copper and glass that looked like lacework but whose struts must have been the thickness of a city block. It commanded the horizon like a fallen moon, and was strung with banners and limned from within by a green-gold glow. The great dome sat at the heart of a cluster of smaller spheres, bubbles of stone and metal that adhered to the central structure, bristling with arched bridges and needlethin towers.

“Who lives there?” Cooper asked, pointing to the dome that dwarfed everything.

“In the Dome?” Asher wrinkled his nose. “Fflaen the Fair—at least, he used to. The Prince.”

“Oh,” Cooper said.

“He rules here.” Asher bobbed his head and said no more, gaze lost in his city.

“Where is here?” Cooper asked at length, trying to keep the welling terror from his voice. The gray man didn’t answer his question. Instead, his eyes drifted to the distance. Fires flickered out there, in the towers of the city. Towers that burned but never fell.

That was a sight that made Cooper’s gut twist. Could he hear crying? He looked to his acquaintance. “Where is here?” he asked again.

Asher’s eyelashes were the color of smoke, and the silence stretched until it became an answer of its own.

Cooper made it back down to the living room in a blur, where Sesstri explained matters more thoroughly. “Listen to me very carefully. This may sound complicated, but it’s not: the life you lived, in the world you called home, was just the first step. A short step. Less than a step. It’s the walk from your house to the barn, and what you think of as death is nothing more than the leap up into the saddle of your trusty pony. When you die there, you wake up, well, not here usually—but someplace else. In your flesh, in your clothes, older or younger than you remember being, but you, always you.”

Cooper nodded because it was all he could do.

“There are a thousand thousand worlds, each more unlike your home than the last. Where you end up, or how you get there, nobody really knows. You just do. And you go on. Dying and living, sleeping and waking, resting and walking. That’s how living works. It’s a surprise for most of us, at first. We think our first years of life are all we’ll ever see.” She paused, her thoughts turning inward. “We are wrong.”

Cooper said nothing. He was dead and he was going to live forever?

Sesstri considered him and drew a long breath, raked her fingernails through her morning-colored hair. “Life is a very, very, very long journey. Sometimes you go by boat, sometimes by horse. Sometimes you walk for what seems like forever, until you find a place to rest.”

“So…” Cooper drawled, deliberately obtuse because humor seemed the only way he could go on breathing. “I have a pony?”

Asher chuckled. Sesstri didn’t.

“There is no pony!” she snapped. “The pony was a mere device. In the country of my origin, we smother our idiots and mongoloids at birth. You are fortunate to have been born into a more forgiving culture.” Asher’s chuckle grew into laughter.

Sesstri rested her palms on her knees and made an obvious show of being patient. “Let me say this as plainly as possible. There are a nearly uncountable number of universes—universes; mind you, when we speak of ‘the worlds’ we speak of whole realities—most of which are populated to a greater or lesser extent with people. Universes with planets that are round, or flat, or toroid—and others with space that conforms to no geometry or cosmology you or I would recognize from home. On most of these worlds, people are born, and live, and die. When we die, we don’t cease to exist or turn into shimmering motes of ectoplasm or purple angels or anything else you may have been brought up to believe. We just… go on living. Someplace else.”

“People call it the ‘dance of lives,’ ” Asher interjected, miming a jig.

Sesstri cocked her head for a moment as if tucking away a fact, then widened her eyes to ask if Cooper followed her so far. He nodded, hungry for Sesstri to continue even though he had already swallowed a bellyful of follow-up questions. Toroid? Which was it, worlds or universes—or was that distinction itself subject to variation? She was a much better instructor than Asher, and Cooper’s only option was to learn.

“There’s little logic behind where we go, although a great many thinkers have spent a great deal of time failing to prove otherwise. I might have succeeded. We live and die, then wake somewhere new. We live on, die again, then wake once more. In a sense you’re right—it is a kind of prison sentence, and life will exhaust you at every opportunity. It’s a slow and painful way to travel, but that’s life: painful and slow. And very, very long.” When she finished, she looked at Cooper with a mixture of doubt and expectancy, waiting for the inevitable reaction of shock and confusion, but it did not come.

“Welcome to the Guiselaine!” Asher sang out, his arms spread wide. “The best worst district in the whole nameless sprawl.” He and Cooper stood atop a brick bridge that straddled a foaming brown canal. Foot traffic, rickshaws, and carts of every design pushed past them toward the warren of crooked alleys and side streets that comprised the Guiselaine, and Asher grabbed Cooper’s wrist, pulling them into the crush. Cooper resisted, but Asher dragged him along anyway; the man was strong. The crowd eddied around a small fountain square at the far side of the bridge before swarming into a tangle of shadowy lanes where the walls tilted overhead, hiding the sky behind half-tunnels of stone and wood and daub.

The two men waded through a river of dirty faces, citizens of a dozen flavors—the rich mixed with the poor mingled with the alien, all distracted by conversation or the challenge of a swarming market at noon. Asher steered through the crowd expertly, his gray face and whitecrowned head breaking above the rabble like the prow of a ghost ship, fey and proud—a ship of bones, a ship of doves.

“The City Unspoken has many quarters, but for my money, the Guiselaine is the one to see,” Asher confided to Cooper as they ducked onto one of the broader thoroughfares. “A most deplorable gem of a borough.” He waved a gray hello to friendly faces Cooper was too distracted to make out. “All tangled streets and hidden treasures. Harmless fun during the day, quite another story after dark. Which is, of course, when I like it most.” Asher spread his hands in a mock-spooky gesture, and Cooper grinned in spite of himself. He took Asher’s hand and gripped it tightly as they darted through the busy world. Whatever had happened to him had dispossessed him wholly, and Cooper found his head full of odd whispers. The crowd didn’t seem to help.

They stopped to stare into the window of a shop that displayed an array of the strangest stemware Cooper had ever seen: scrimshawed goblets carved from human skulls, pale leather wineskins that bore the sewn-up eyes and mouths of human faces, and a ghastly masterpiece that dominated the display—a silver decanter set within the corpse of a toddler boy, plasticized by some grim process, whose split skull and abdomen cradled the silver vial while shining filigree slithered around its chubby limbs. It looked like some metal parasite had emerged to gorge itself upon the child, slipping silver tentacles around every spare feature of flesh. Looking at the decanter, Cooper felt detached from the horror, somehow, his head running a line of practical questions. How do you cleave a child so cleanly from crown to belly? How do you work silver so intricately, without burning the flesh or ruining the composition? How do you get a child to make such a beatific expression as you bisect the front of his face? There was no life here to sense, no sensitivity. Just art, artifice, and commerce.

Those were things he could understand, at least. He’d spent most of his life thus far as a consumer—why should life change, wherever it went? Wasn’t that the gist of Sesstri’s lecture?

“Come on, Cooper,” Asher complained, tugging at the newcomer’s wrist. “Bells, but you’re slow.”

A man with black skin—not brown, black—knelt over the body of a child, a boy, who stared at the sky with an uncomfortable intensity. ComeOnSabbiComeOn, the man said, except he didn’t. Cooper wasn’t close enough to hear and, in any event, the man hadn’t moved his lips. SabbiSabbiLookAtDaddy, Cooper heard again as they neared—the man felt terrified.

How do I know what that man feels? Cooper asked himself. But he did.

Cooper looked to Asher to see if he’d heard, too, but Asher appeared oblivious. Cooper looked to the black man as they passed him, but the man did not even see them, cupping his son’s cheeks in his carbon-dark skin. SabbiComeBackAround! DaddyNeedsYou!

The passersby did not hear, either. Cooper thought he would have known if they heard the man but ignored his suffering, because he saw that every day in New York. No, he’d heard words that hadn’t been spoken. Him, and only him.

“Asher,” Cooper began, beginning to freak out as they turned a corner into a ramshackle courtyard where a dusk-skinned woman in a tattered dress leaned against the wall by an alleyway, pressed by a rat-faced man with bulging eyes and shaky hands. Her hair was curled and coiled atop her head but was caked with dust—like a wig left out of its box for a decade or two.

Something stopped Cooper in his tracks. Asher looked back, impatient, but Cooper stared in horror at the woman and her accoster, distracted from his own thoughts.

She had a sad face painted brightly to obscure the truth, and she laughed like a schoolgirl every time the small man spoke, flashing a smile that never touched her eyes. He cupped a hand to her breast and she held it there, whispering encouragement. He drew a lazy line across her throat with one finger and dripped words into her ear. She licked her lips and pressed against him, but inside she was screaming. Cooper knew, because he could hear it.

NoNoPleaseNotAgain. He could hear it. Words that weren’t spoken. Fear.

NoNoNeverICan’tBreathe ICan’tBreatheKillMePleaseKillMe, KillMeDead, AndMakeItStickThisTime, MakeItStickThisTimeICan’tBearToWakeUpAgain.

“Stop it!” Cooper yelled, dashing forward. “Stop! Asher, help, he’s going to kill her!”

Asher barked a laugh, and caught Cooper’s arm as he shot by. “Of course he is, Cooper.” He waved an apology to the woman and the ratfaced little man. “Apologies, do carry on.” They did.

Asher pulled Cooper close and growled, “Please don’t do that. You neither know our customs nor have the moral authority to intervene. And you make me look bad.”

“What is she?” Cooper asked, aghast, as the woman and her paramour withdrew into the gloom of the alley.

“She’s a bloodslut,” Asher said coldly, but his eyes were downcast. “A life-whore. A stupid girl who signed the wrong contract somewhere along the way, and now she’s stuck here. She can’t die, so she sells her body and life to any jack with two dirties to rub together. He ruts her, guts her, then fills her mouth with coins.”

“Wait, what?” Cooper’s brain couldn’t quite gear itself up for the question of death. That poor woman didn’t seem dead, merely exhausted. But her thoughts, if that’s what he had heard… her fears…

“She can’t die,” Asher said, pointing to a pair of figures picking each other up from the dirt. One kept her gaze low, the other leaned against the bricks trying to catch his breath. Both looked too thin, too worn. “Not properly, anyway.”

“That’s horrible.” Cooper was shivering. “Her job is to let dirty little men kill her for money?” He couldn’t keep the disgust from his voice— what pathetic creature could survive that way, let alone turn a profit? Then again, if she couldn’t die, he supposed she had no choice but to survive. If that were the case, maybe it was no wonder her brutalized thoughts scraped the inside of his head.

Asher nodded. “Kill her, and whatever else they want to do to her. For money. Why else? Hurry up.” Asher nearly dragged Cooper down the street as bells began to toll in the distance. Bells and bells and bells, a city of them.

But Cooper’s thoughts were back in the alley with the woman who looked more… used than should have been possible. Here that seemed to be normal. What other nightmares were normal, here, that should be awful? Was hearing the fears of strangers as inconsequential as screaming inside, screaming for peace? He’d heard her, heard her panic inside his head. What did that make him? Deathlessness aside, Cooper couldn’t figure out what unnerved him more: the contents of her head, or the fact that he’d been exposed to them.

A few moments later came a brain-piercing scream that trailed off wetly. No one on the street seemed to notice. Asher saw Cooper’s discomfort, flashed his winning corpse smile, and pinched Cooper’s arm. “Don’t worry, really. A few hours from now her body will jerk upright, skin whole if not new—she’ll spit out her wad and be open for business again.”

“Oh.” Cooper’s stomach convulsed and he nearly tossed his toast. “No wonder she was screaming.” He smelled fried bread and crispy fish from a hawker they passed, and swallowed hard.

Asher gave him a funny look. “It’s just a little death, Cooper.”

“So death means absolutely nothing.” His body felt numb.

Asher shook his head. “No, that’s not at all what I—”

“—All my life, all everyone’s life, we’re so scared of—what, a travelogue? Death is a game, just part of the economy, and my life means— meant—means nothing?” Cooper bit out the words accusingly, like the City Unspoken and its deathlessness were all Asher’s fault.

Asher put his hand on Cooper’s chest and pressed him into the brick wall of the lane. His force was controlled and guided, just this side of dangerous. “Don’t say that. Don’t say that; death is the worst thing that can happen, so don’t ever say that.” This, too, passersby ignored; these were a people inured to every kind of disturbance. Had any of them been New Yorkers, once?

Cooper let that fuel his indignation. This metropolis was worlds worse than ignoring indigents and stealing taxis. “The worst thing that can happen is a nap and a brand-new body, are you kidding me?”

Anger clouded Asher’s gray face. “Every time we die, a whole world dies. What do you think they’re saying about you right now, Cooper?” Asher shook his head in disbelief. “Is it ‘Oh, Cooper stepped off to another universe for a brief visit but we expect him to return shortly. Canapé?’ Or do you think there’s a funeral somewhere with your fucking name on it?” Asher was livid, but his skin showed not a pulse of blush. He let Cooper go, who doubled over at the thought of what his family and friends must be feeling.

Now came the fear and confusion that Sesstri had expected earlier. Cooper pictured his mother, obliterated by losing her only son. His father, cracked in half with grief. Life had been dull, but it had been. Cooper’s head reeled. How could I forget that? he screamed inside. How could I, for one single moment, doubt the totality of my death, back in the world where I lived?

“I apologize,” Asher nearly stammered, “I associate honesty with anger. It… explains a lot. Are you crying?”

Cooper couldn’t breathe. His family and friends—what nightmare must they be enduring? Sheila and Tammy would be screaming when they found his body in the apartment they shared. Mom would be turning in place, trying to put right something that could never be fixed and was the heart of her world. His dog, Astrid—would she sit by the door, waiting for him, wondering why he never came back to her? She wouldn’t understand, just ache. The same went for Cooper as for those he’d left behind. No understanding, just pain and loss and a false promise of peace at the end.

“This is sickness,” he choked from his knees, “how could they not be my first thought? This is sick, sick, sick.” He looked up at Asher, stringyhaired and chisel-faced, the piss-colored sky going blue behind him. Quicksilver clouds gathered, not minding the schizophrenic heavens above them. “Can’t you see how sick this is, or are you too dead to notice?”

The colorless man closed his eyes and took a breath. “There are sicknesses. Living is not one of them.” He fixed Cooper with a tight-jawed expression. Asher’s false levity had fled.

Cooper stood up, wiped his eyes, and crossed his arms like an obstinate child. Despite the death and deathlessness, despite the bloodslut’s impermanent murder, he found himself. Despite the background noise of fears murmuring in his head as people passed. “Explain. Now. I can deal, if I know.” Cooper leaned against a wall so ancient its bricks had crumbled into little pockets for weeds and moss. “Am I really dead or only dreaming? I feel awake, but… Am I in a coma? Is this some kind of fucked up comaland? Sesstri says I’m dead. Are you dead? What’s with the urban purgatory? What’s with the—”

“Okay, okay.” Asher held up his hands in defeat as a meatmonger glared at them, two jackadays blocking her passage through the narrow lane. “Walk with me, and let this nice woman get on with her deliveries.” Cooper thought Asher wanted to flee.

A cart filled with wrapped bundles dripped watery blood as it trundled past. Its minder cleared her throat in disapproval. He looked at the butchered meat and considered his body, lifeless and cold somewhere so far away that distance wasn’t even the proper metric.

“On…on Earth we don’t…we don’t wake up after we die.” It sounded so stupid, so utterly unhelpful.

“Earth?” Asher crowed. “You named your home after dirt?”

“Hey, fuck you.” Cooper frowned. “You’re supposed to be filling me in, not attacking my cultural heritage. The afterlife is hard enough as it is.”

“What’s after life?” Asher asked, sincerely, indicating a trio of passing shoppers laden with brightly colored bags, who turned up their noses. “There’s only life.”

“That doesn’t make any sense,” said Cooper, his bewilderment starting to burn into anger. That was good—anger he could handle, anger was familiar. “If I lived, and I died, then this place—whatever it is—must be the afterlife. It’s after my life, isn’t it?”

“No! Blessed batshit bells, it’s just the beginning; that’s what I’m trying to show you.” Asher screwed up his face as if choosing his next words carefully. “You live and you live and you live, and one day, maybe, if you’re lucky, you get to stop.”

“I just don’t believe it. I can’t. You and Sesstri, you say that whenever someone dies, they just… wake up somewhere else?” Cooper grimaced and imagined a hundred wakings like he’d had today. A thousand. “Are… are you dead too?”

Asher scoffed. “I’m older than dirt.”

How could Asher be so cavalier about something so revelatory, Cooper tried to understand. Then again, if what he said was true, who wouldn’t be jaded by a thousand thousand weekdays?

“And then they die again and wake up somewhere new, again and again and again?”

“Most of ’em. Most of the time.” Asher’s face flickered with a frown before his mask of gray cool reassembled itself. He held his arms against his ribs in an uncomfortable-looking way for just a moment longer, taking deep breaths. Cooper realized that this was hard for him, too.

“Right.” Cooper scrubbed his face with his palms. “Except the bloodslut, she stays here.”

Asher nodded. “Correct.”

The dam burst and Cooper’s questions erupted without pause: “Do we all go to the same places? What happens if we don’t want to start all over again? Why did I wake up with my clothes on? Do people just… wake up on hillsides like that? Where do our new bodies come from? How did you know to find me there? Are you some kind of social worker? And why me, why are you helping me, when millions of people must be—”

“Breathe.” Asher put his hands on Cooper’s shoulders, but the instructions were useless.

Cooper’s mind had initiated a kind of cascade of possible weirdnesses: accepting that he wasn’t dreaming or comatose and that he most definitely was strolling down a cobbled road where a prostitute had just been murdered as part of a routine transaction, was holding the arm of a madman, was hearing whispers inside his head—what possible flavors of the bizarre should he be preparing for? Dragons? Zombies? Dark Lords or Evil Empires? Mind control? Trickster gods or elaborately plotting aliens? The options fell away one by one, rendered inadequate by the chromecolored clouds and the spirit of the bloodslut still shuddering inside her body. Cooper realized that despite his lifetime of escapist education, a tacit understanding of his own ignorance would be the only benefit for which he could possibly hope.

Asher seemed oblivious to Cooper’s internal cataclysm. “You’ll learn everything about it soon enough. No, we don’t all follow the same path of lives—we go where our spirits are drawn, so one life is rarely too different from the next. We are who we are, forever. Often we wake up younger, sometimes much younger, but also sometimes older. There’s a certain amount of chance to everything, Cooper.”

“What’s this ‘each life not too different from the next’ load?” Cooper pushed Asher away and threw his arms out wide. “I’d say this is pretty fucking different from what I’m used to!”

Asher paused. “With exceptions, obviously: the brave, ambitious, or”—here he gestured at Cooper—“the unlucky witless.” Then, changing the course of the conversation, “But there are other kinds of exceptions, like the body-bound, for instance, including the bloodsluts and most members of city government. They’re bound by contracts to this world, this city, and their own inescapable bodies.”

Cooper felt aghast and relieved at the same time—relief that the smalltown fictions of god and heaven from his childhood were as imaginary as the space ninjas and Japanese manga of his young adulthood, and aghast that not one single experience of his life before could possibly have prepared him for this day. Even his acid tongue was useless.

“And all this living, then, Sesstri said it wasn’t endless? That this city… that the City Unspoken is where people come to actually die, for real?”

“Yes.” Asher explained as kindly as he dared. “People live as long as they need to live, whether they want to or not. Toward the end, there is a… a kind of pilgrimage. There are different ways to end yourself, if that’s what you really want, but only True Death offers complete oblivion. And there are only a handful of places in the worlds where True Death is possible for those in need, although it can be a difficult blessing to obtain.” And then, “More so, lately.”

“Why?” Cooper felt his questions drying up in his throat. This was too much; he didn’t remember dying, and he couldn’t imagine… what he couldn’t imagine. The fears of others that murmured inside his head were drowned out by his own.

“True Death is only granted to the deserving few. You can’t just be suicidal, you have to have earned oblivion. And there are very few places where the gates to True Death are open. This city is one of those places. The oldest, if you believe the state propaganda, but certainly the most infamous. We are the crown jewel of ultimate obliteration.”

“Oh,” said Cooper, listening to his fears.

They walked in silence after that, and Cooper reassembled his self-possession by trying to orient himself geographically. He soon realized that tangled as the Guiselaine was, it had a certain logic to its construction. Each street seemed to be dedicated to one specific purpose—he and Asher darted down a lane lined with shops that sold only women’s shoes. Boots of every shape and condition were displayed below razortoed heels, beside fur-lined moccasins, rusted metal clogs, and slingback fantasies. The street after that held birds of all conceivable varieties perched on wire stands, bound by chains, or within cages. The air shimmered with clicks and caws and the cries of the falconers, swarthy brutes in leather greatcoats who held their most prized beasts on gloved wrists.

“How can you find your way through this termite’s nest?” Cooper broke the silence as they took another shortcut. They’d taken so many turns in such a short span that Cooper thought for certain they must have doubled back on their path at least half a dozen times, but he’d seen no repeated intersections or blocks he recognized.

“Sense of smell,” Asher answered, then reached into his pockets. “That reminds me. Take these.” He filled Cooper’s hand with octagonal coins of several sizes. “For later.” Cooper heard a finality in Asher’s voice that made him uneasy.

“Money. Thanks.”

“The big ones are dirty silvers, the smaller ones are nickeldimes. One dirty will get you a cheap meal. A nickeldime buys a rickshaw ride to just about anywhere. Don’t pay more than five dirties for a room or you’re being robbed blind.”

“Thank you, Asher,” Cooper said, bemused by the generosity. “But I think I’ll stick close to you for the time being.” He poured the coins into his empty pocket; when he’d lain down on his bed back home he’d had a stick of lip balm in his jeans, but discovered now that he’d lost it. Which was just great—Cooper was dead with the papery lips to prove it.

A man with liver-yellow skin and bloodshot eyes stumbled out of a storefront, screaming incoherently. Beneath his matted hair his face was wild, twisted, and he wore a strange kind of suit that looked far too new to be as filthy as it was. A woman in culottes and a faded t-shirt was shouting at the rabid-looking man. “Get out, you crazy pilgrim, your Dying insanity is bad for business!” She shooed him away. “Bells! What do you want with bridal veils, anyway?”

The stranger lurched first in one direction and then another, taking a strange tack-and-jibe approach to walking. When he saw Asher, he winced, and his eyes slid sideways to Cooper with a kind of relieved hatred. He threw himself forward, hands reaching for Cooper’s throat.

Asher acted several beats more quickly. He pivoted on one foot and planted the other between Cooper and the madman, while reaching out with one long arm to wrap his hand around the man’s neck—tripping and choking the lunatic at the same time. It happened so fast that Cooper saw Asher as a blur of smoke, moving more swiftly than any normal man. His assailant came to a full stop with a sickening popping sound from inside his neck. With Asher supporting most of his weight from his gullet, the man made a choking sound and began to claw at the air— although the length of Asher’s arms kept him at a safe distance.

The deranged fellow glared at Cooper and raged, trying to shout through a half-crushed windpipe. “You have one!” he rasped. “Oh, oh, you should not be here. The darkness… you see the darkness, you hear the fright! The darkness in the depths can never be held to light. We Die, we live! Exult, extinguish!”

Asher threw the man—by the throat—across the street, into a row of trash cans. “Fuck off, pilgrim, or I will carve you into pieces.”

The man lay there amidst the trash, moaning. SisterWhereAreYou? Cooper heard the man clear as day. ICan’tHearYouAndItHurtsMe, Sister! His fear was an alarm bell. AstarnaxMySister ItHurtsToLiveWithoutYou IAmSoAlone.

“I lost my sister,” the man whimpered, aloud, to his trash-can pillows.

Cooper remembered Asher’s admonitions and held his tongue.

“I did not lose my sister!” he screamed, suddenly incensed again. “She was stolen from me! Or she… she Died. Did I? I didn’t Die, I couldn’t Die. Nothing happened but more heartbeats inside my haunted chest. Where did my sister go? Astarnax? Astarnax, where are you?” He was laughing now, looking around blindly like he was losing a game of hide-and-seek. “Why did you steal my sister? Why?” Cooper-OmphaleIBlameYouBlameYou!

Cooper was dumbstruck. How does he know my name? “I…I…I didn’t do anything to your sister,” he stammered.

“Liar!” the man screeched, a raptor’s cry. Window glass shuddered in its casements along the length of the street, a ripple of pain. The flow of the crowd juddered; everyone had felt that.

A moment of wretched silence passed before Asher pulled Cooper away, instantly lost in the crowd and hurrying from the crazy, too-knowing man. Cooper tried to gather himself, but his self did not want to obey. Too much, too fast, too wrong.

He grasped for a thought to ground him. A memory. Something green. He tried to remember his parents’ home in the summer, tried to picture the gardenias that grew so big and waxy, the heirloom irises from his mother’s childhood home, their purple flowers faded almost white. He tried to see the light through the windows as it fell on the desk in his father’s study. Yes. He had a green leather blotter with brass studs, and if you wrote on it you had to press very softly with the pen because he didn’t want to score the leather. Cooper knew these things still existed, but they were no longer his.

“What was wrong with that man?” he asked, walking in the lee of Asher’s arm down the street. How did he know my name? And what was that other thing he called me? Alm Fail? What does that mean?

“Ignore it.” Asher’s tone was clipped. “It’s nothing you need to worry about. The man was a con artist. He tailed us, or something. Whatever you do, don’t let crazy people on the street make you question your own sanity. In all likelihood that’s how they got that way.”

“Why does everyone seem to want to die?”

Asher merely shook his head. His eyes darted around as if looking for an escape. “Watch out for the crazies.” They passed two grimy men playing cards on a rubbish bin. Asher dipped his head in their direction and added, “And watch out for the swindlers. Don’t be a fool with your money.”

Cooper snorted. “I’m not an idiot—money is money. But what are they playing?”

“Three Whores. It’s a scam, can’t be won.”

“Okay,” said Cooper as they turned down yet another side street. “Then why would anyone play?”

“Why does anyone ever gamble?” He gave Cooper a sideways look. “Don’t your people enjoy things that are bad for them?”

When Cooper didn’t answer, Asher gave him another, more searching look. Cooper couldn’t help but notice the perfect proportions of Asher’s gray face, or the squared lope of his shoulders.

“What happened to you, Cooper?” Asher asked with an edge of intensity.

“How the fuck should I know?” Cooper threw up his arms. “Am I not the clueless one here? Wherever here is?”

All of a sudden, a clamor of wheels sounded from behind them. Asher threw Cooper face-first against the stone wall and held him flat as something big and fast and loud rushed down the cobbled lane at their backs. Startled, Cooper strained his neck to see a massive black-lacquered carriage bearing down the street like an angry bull made of gilt and teakwood—scattering hawkers and hausfraus alike lest they be crushed by its cherry-red wheels. As the carriage rushed by, Cooper saw a woman’s hand with blue-green nails dangle from a red-curtained window. The hand twitched as the vehicle passed, and for an instant a finger pointed directly at Cooper’s heart.

He stared at the receding, accusatory finger while Asher narrowed his eyes in distaste. A tattooed rickshaw driver stood drenched in sodden filth, shaking his fist and hurling unintelligible curses after the carriage. Across the street, a matronly woman held her hands to her head and despaired at an overturned bushel of bright green apples, gemlike fruit spilled into the mud.

“Dead gods fucked, fed, and flattered!” Asher cursed with a sneer. “What the fuck was that?” Cooper demanded. “There goes Lallowë Thyu, second wife of the Marquis Oxnard Terenz de-Guises, who ‘governs’ this precinct.” His eyes flickered red with hate and he stood motionless, glaring at the bulk of black opulence as it careened around the corner. “Sic transit pure evil.”

“Uh-huh,” Cooper mumbled, not really in the mood for local politics. “Well, your pure evil just pointed a finger at me as she hurtled past.” The finger had pointed at him, he’d felt it.

Asher paused and gave Cooper a curious look, half-accusatory, half-hopeful.

“You didn’t see that?” Cooper asked.

“Of course I saw it, but you’re imagining your own significance.” Asher scooped up an armful of apples and returned them to the grumbling woman, who handed one back with a nod. “Thyu has no reason to know you exist, and if you’re lucky she never will.”

“Then what was she pointing at—you?” Asher hid his face behind the apple. “Of course not. She has no reason to know I exist, either.” He didn’t

sound convincing. “Apple?” “What then?” Cooper caught the green fruit as Asher tossed it in the

air and spun around, continuing down the lane. Asher snapped, “She’s a greedy bitch who’d grind her heel into half

the city if she could. Lallowë Thyu is the worst kind of aristocrat. The kind whose foreign beginnings—which ought to make her a gentler citizen—only fuel her insane hunger for status, power, and things.” His fists were clenched and he looked very much like he wanted to make a run for it. “I hate things.”

“Not much of a materialist, are you?” Cooper teased the gray man’s back as he walked away, then crunched off a bite of apple. “Or a royalist?” It tasted just like an apple should taste, which somehow put him at ease.

“Royalist?” Asher spat. He did not sound friendly now, not at all. “No! No, I am not.” He paused as another carriage came tumbling down the alley, this one a windowless commercial lorry. His eyes lit up. “Bells. I’m not a lot of things, Cooper. For instance, I am not your friend.”

“What does that mean?” Cooper asked, feeling a stab of fear and a lonely realization, but Asher only shook his head.

“Sesstri’s right—you’re not what I’m looking for, Cooper. I’m sorry. I have other failures to fix. I hope I gave you a bit of a head start, kid, but you’re on your own. Just like everyone else.”

Asher reached out and grabbed the corner of the lorry as it rolled by, stepping up onto the footman’s perch. Cooper just stood there, gaping as wordlessly—as he had earlier that morning on the hill above Displacement—watching the carriage speed away with the tall grayskinned man who had been Cooper’s only hope.

“Don’t forget all we talked about,” Asher called out. “You’ll need it.”

The Waking Engine © David Edison, 2014